|

Page A3 / The Joan

De Arc Crusader / Wednesday, December 25, 2024

Front Page

A1

/

Editorials A2 /

Christmas Nostalgia A4 /

Crossword

A5

A

Joan De Arc kid’s epic correspondence with Parker Brothers Inc.

By J. Bueker

My

childhood infatuation with games of all sorts met with a decisive turning

point in the late 1960s when our mother began frequenting the remarkable

little thrift stores hidden away in Sunnyslope with her kids in tow. For it

was there I experienced a most startling revelation: an amazing array of

antique Monopoly

games dating clear back to the 1930s and 1940s. I’d no idea the game existed

so far into the distant past and I quickly became utterly fascinated by

these early examples of the famous Parker Brothers pastime.

Thus commenced my legendary obsession with procuring every possible ancient

edition of Monopoly

on which I could lay my greedy hands. At first only mildly interested in

accompanying Mother to the dusty old Sunnyslope thrifts, I now viewed those

quaint little shops as a frightfully imperative destination and I would make

an immediate beeline for the toys and games section upon entry to each

establishment.

Parker Brothers of course had

been the gold standard in board games for many years, peaking in the decades

following their momentous acquisition of

Monopoly

in 1935. Among the company’s legendary offerings were the immortal

Sorry!,

Clue,

Careers,

and Risk,

in addition to popular card games like

Pit

and Rook,

games that would help to define my very childhood. I also became enamored of

somewhat more obscure Parker titles like

Dig,

Finance,

and Camelot,

relics from the past that enjoyed significant popularity in the ‘40s and

‘50s and could also be found gracing the shelves of the Sunnyslope thrifts.

The singularly renowned and ubiquitous Monopoly

however held a unique place in my esteem and no other game could remotely

approach its unchallenged prominence. I’ve innumerable memories of this

timeless cultural icon stretching back to my very earliest years, long

before we ever came to Arizona, observing my siblings playing the game back

in Michigan and studying the distinctive and intriguing board and playing

pieces. By the time we were ensconced on Joan De Arc, I was actively

participating in the fun.

The Goodwill thrift at

Hatcher Rd. and Central Ave. was a particularly fruitful source for old

Monopoly

sets, including the glorious version that would quickly become my favorite

to this very day: No. 9, also known as The White Box Edition, the deluxe

Monopoly set issued throughout the ‘40s and into the ‘50s. The No. 9 set

featured fancy Grand Hotels with gold lettering, a luxuriously embroidered

game board, and a double supply of play money, among other extravagant

accoutrements. The beautiful textured white box was adorned with that

whimsically cool cartoon of one man chasing another down a street in

apparent pursuit of his money. My first White Box from Goodwill was a

shining milestone in my blossoming game collection career, and within a year

I was the proud owner of around a half dozen various antique

Monopoly

sets.

My family was puzzled by this behavior. It

was very unclear why I felt the need to possess multiple copies of this

game, or any game for that matter, and since the Buekers had for years

already owned a copy of the 1961 standard edition, we technically didn’t

need any additional Monopoly

sets at all. My emerging collector mentality seemed genuinely inexplicable

at the time, and when I started lugging all those old games home from the

thrift stores, it was thought to signify one of my more notable childhood

eccentricities.

So now that I was an official

Monopoly aficionado, I naturally became interested in how it all began. Who

conceived of this marvelous game? What did it originally look like? How has

it evolved over the years? What accounts for its unprecedented popularity?

Craving detailed information about the history of

Monopoly

and the ultimate genesis of the game, and lacking an Internet to gather this

information, I came upon the idea of simply approaching Parker Brothers

themselves directly by sending a letter outlining my inquiries. I strongly

suspect one of my parents interceded to suggest this course of action,

though that particular memory now seems to have faded from my slowly

degenerating brain cells. But I was also expertly familiar with the contents

of the game’s printed set of rules, on which was clearly stated at the very

bottom: “Questions on this game will be answered gladly if correct postage

is enclosed.”

I therefore summarily crafted and

sent off a brief missive in August of 1969 requesting of the manufacturer

some basic historical information regarding their celebrated game. I

probably just addressed it to the location listed on the game boxes, “Parker

Brothers, Salem, Mass.,” confident my message would find its way into the

right hands. I was decidedly uncertain that I would ever receive any sort of

response, but it didn’t take long to find out: perhaps but a week later, an

official-looking communique from the famous game makers appeared in the

mailbox at 3219.

Thrilled beyond compare, I

immediately tore open the letter and excitedly absorbed its contents.

Parker’s reply comprised a brief synopsis of

Monopoly’s

history, acknowledging a fellow by the name of Charles Darrow as the game’s

inventor and early advocate, a salesman turned savvy game entrepreneur who

solicited Parker in the mid-1930s to assume publication of his game as sales

became increasingly unmanageable. The letter also noted that while

Monopoly

was the most popular board game in the world, it was officially banned in

Russia and Cuba, an interesting reminder of the ongoing Cold War and the

game’s undeniably robust capitalistic nature.

Monopoly

wouldn’t be published in Russia until 1988 on the very eve of the Soviet

Union’s dissolution.

Only many years later would I

discover that the “history” of

Monopoly

that Parker Brothers had so carefully cultivated since their purchase of the

game was somewhat more fable than reality; turns out the origins of the

thing were significantly more complex than the Parker boys were letting on.

Monopoly

actually derives ultimately from

The Landlord’s Game,

a rent and tax board game that was created in 1903 by one Elizabeth Magie as

an educational tool to illustrate certain economic principles. The game then

passed through a series of permutations before it finally came to Darrow’s

attention in the early 1930s. Charles Darrow does deserve a great deal of

credit for shaping the game into the familiar form we all know and love, and

also for engendering its initial popularity, but he was hardly the inventor

of Monopoly

or its underlying concepts.

Darrow’s

most enduring contribution was unquestionably the distinctive graphic images

he devised for the Monopoly

box and game board. The aforementioned raucous street chase scene on the

game box, the forlorn man gazing out from his cell on the Jail space, the

distinctive railroad train symbol, the Go space with its majestic arrow, the

mysterious Chance question mark – these iconic images were all the inspired

work of Mr. Darrow. While not the ultimate creator of the game, the man

polished Monopoly

into a much more marketable form and made possible its transformation into

the matchless phenomenon it would become. Darrow’s

most enduring contribution was unquestionably the distinctive graphic images

he devised for the Monopoly

box and game board. The aforementioned raucous street chase scene on the

game box, the forlorn man gazing out from his cell on the Jail space, the

distinctive railroad train symbol, the Go space with its majestic arrow, the

mysterious Chance question mark – these iconic images were all the inspired

work of Mr. Darrow. While not the ultimate creator of the game, the man

polished Monopoly

into a much more marketable form and made possible its transformation into

the matchless phenomenon it would become.

While quite delighted with

Parker’s response, I was disturbed to find that not all was copacetic on the

home front. It seems my correspondence with the storied game company had

aroused the indignation of my eldest sibling Susan, who was quick to

register her displeasure at my actions. Sue insisted that the good folks at

Parker Brothers had far more important things to do than cater to the

frivolous requests of some goofy 11-year-old living in Phoenix, Arizona of

all places. Her annoyance only increased when Parker graciously indulged my

desires with their remarkably prompt and generous note. I struggled to

understand my sister’s concerns -- this was the coolest thing ever!

The Parker letter served only to fuel my desire for ever more information on

the game and I decided to risk further condemnation from my sister and relay

a follow-up request to Salem. I was exceedingly curious about the appearance

of the original copy of

Monopoly and so I sent out a

second letter requesting a photo of this holy grail of board games. Sue’s

outrage no doubt attained its zenith at this juncture but I simply could not

be deterred. Again I was unsure I would ever receive a response, but lo and

behold about a week later a large brown rectangular parcel arrived at the

house.

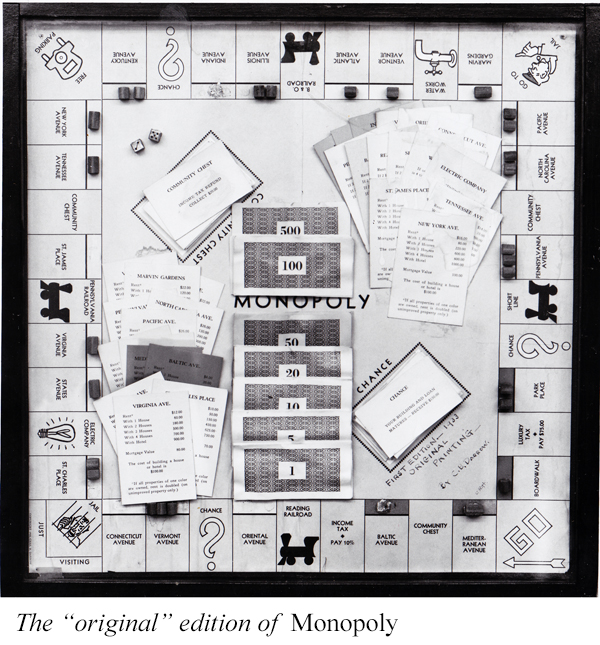

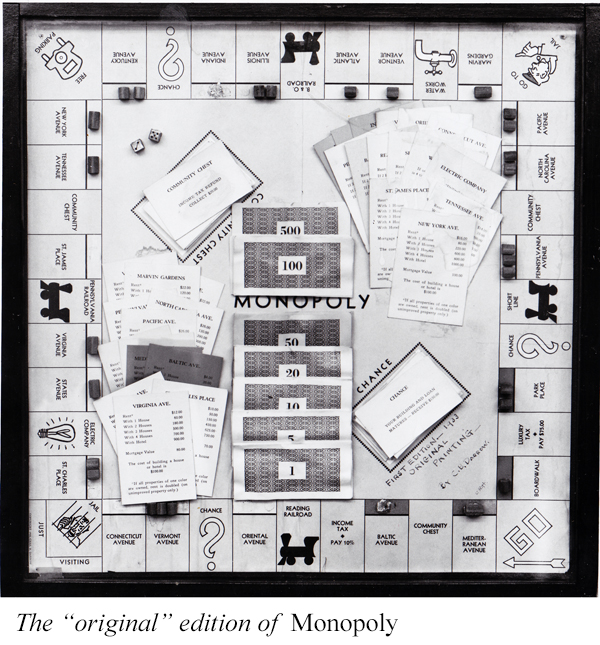

This could only be the highly

coveted photo I had requested of the first

Monopoly

game ever made. I carefully opened the package and withdrew a clasped

vanilla envelope containing not one but two photos. The wonderful folks at

Parker had not only sent along a nice black and white image of what they

deemed the original edition of

Monopoly,

but they also included a cool 8x10 publicity shot of the venerable Charles

Darrow! My Monopoly

cup had officially runneth over. I still have the photos carefully preserved

inside the original vanilla envelope tucked within the brown cardboard

parcel.

Parker Brothers no longer exists

as an independent company, long ago demoted to a mere brand name in the

aftermath of Hasbro’s acquisition of the firm in 1991. I shall however

remain eternally grateful for the patient kindness and thoughtful

consideration the good folks at Parker showed a fanatical 11-year-old

Monopoly

devotee way back in that magical summer of 1969.

Oh yes and I do hope my sister has forgiven me by now.

The "First Baloney Prize" on Joan De Arc

By J. Bueker

My father had little difficulty identifying yours truly as his

offspring most interested in game play, an activity of which he was also

quite fond. The man therefore invested a significant amount of time instructing his youngest child in the rules for the gaming nearest and

dearest to his own heart such as gin rummy, pinochle, and perhaps most

prominently, chess. This ensured for him at all times a readily available

game partner and thus the two of us spent many a night at the kitchen table

in the family room at 3219 engaging in various such game competitions. Yet

there was always something of an exalted quality to our chess matches --

that ancient and sublime game that seems to inhabit its own unique

intellectual plane.

instructing his youngest child in the rules for the gaming nearest and

dearest to his own heart such as gin rummy, pinochle, and perhaps most

prominently, chess. This ensured for him at all times a readily available

game partner and thus the two of us spent many a night at the kitchen table

in the family room at 3219 engaging in various such game competitions. Yet

there was always something of an exalted quality to our chess matches --

that ancient and sublime game that seems to inhabit its own unique

intellectual plane.

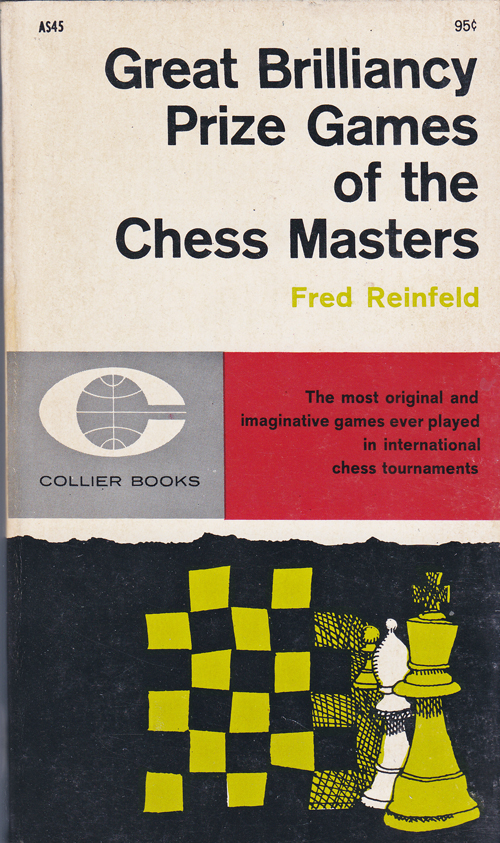

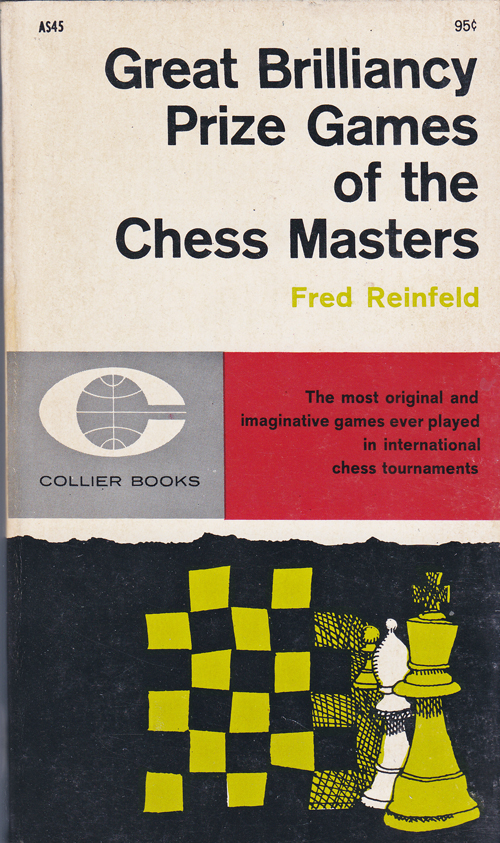

At some point in the ‘60s, Carl’s interest in chess prompted him to

purchase a paperback on the subject that would become a book of primary

importance for me on Joan De Arc: “Great Brilliancy Prize Games of the Chess

Masters.” Written by prominent chess master Fred Reinfeld and published by

Collier Books in 1961, the volume featured the complete notations and

analysis for some of the most creatively conceived games of all time by some

of its greatest players. I was particularly impressed by the “First

Brilliancy” prizes awarded to each of these masterpieces by some chess

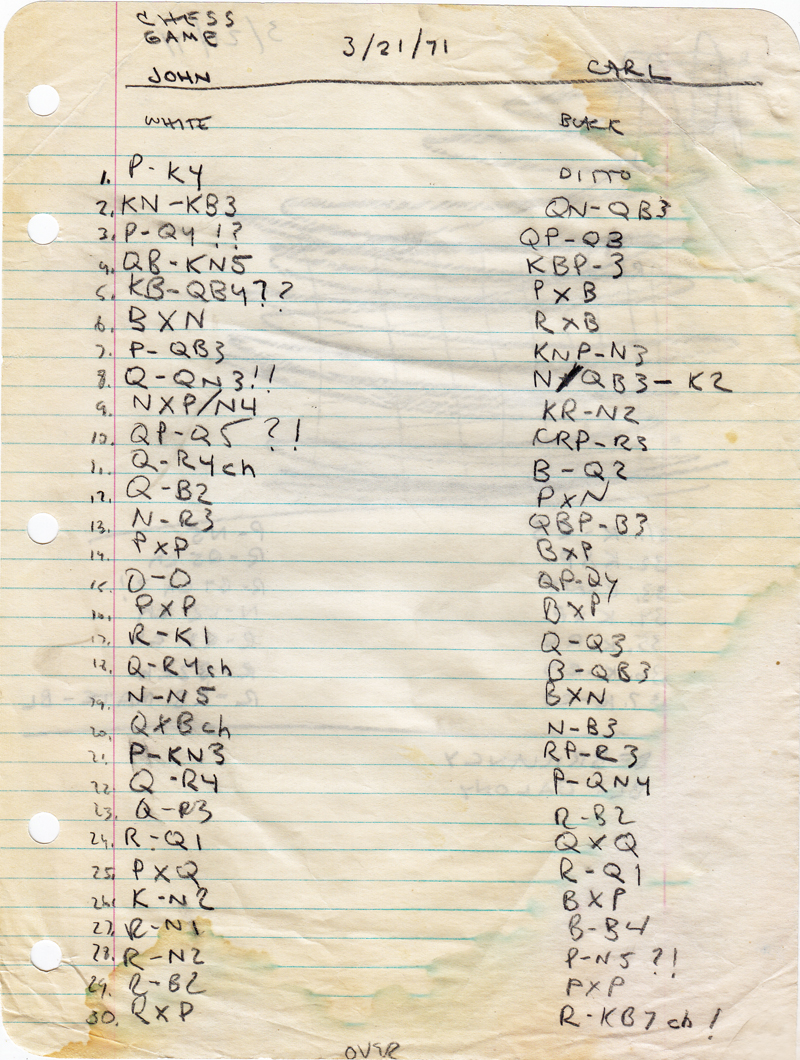

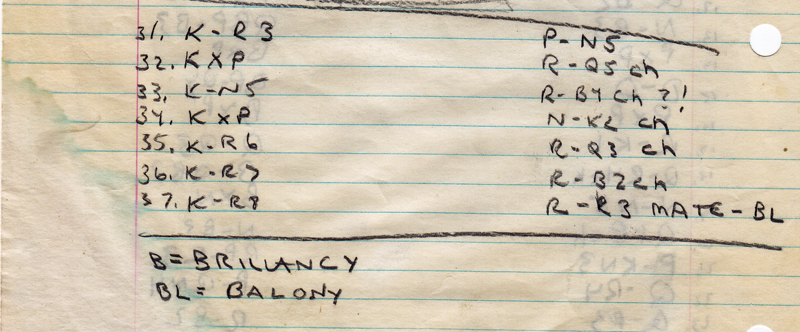

authority or another. Inspired by this remarkable book, I took the trouble

one evening to carefully document for posterity one of my frequent chess

matches with Carl, which he naturally won as usual. Ever the epitome of good

sportsmanship, I awarded my father the “First Balony (sic) Prize” for his

stellar chess performance that night.

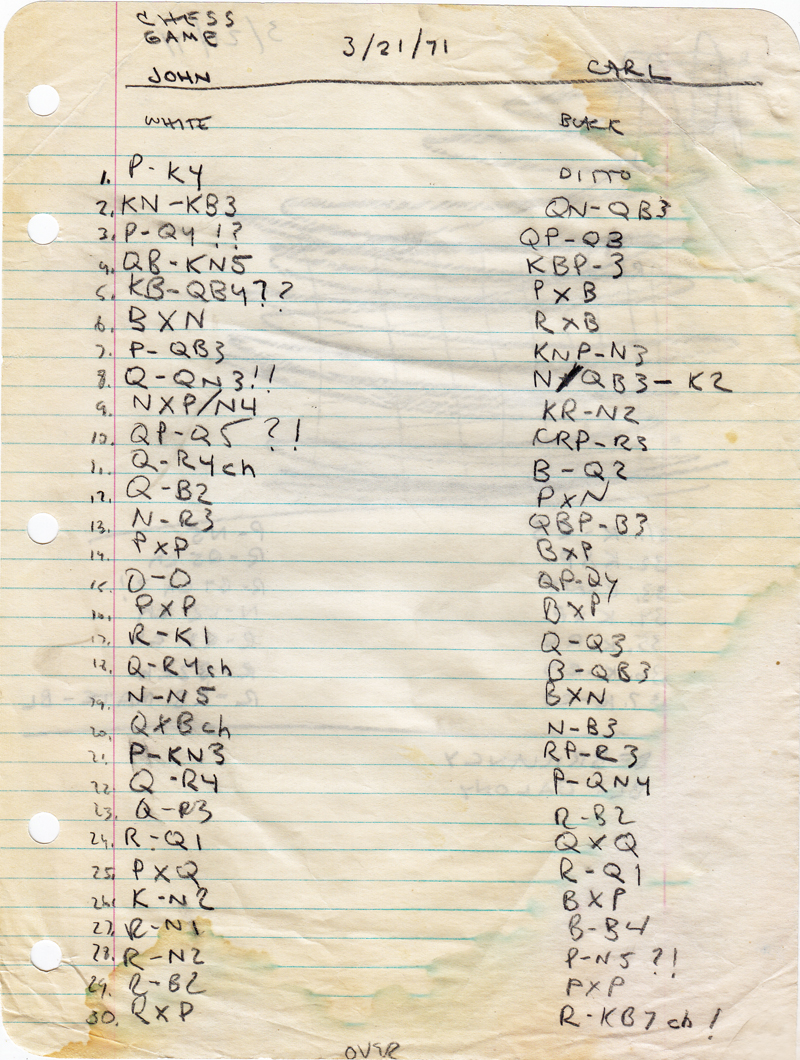

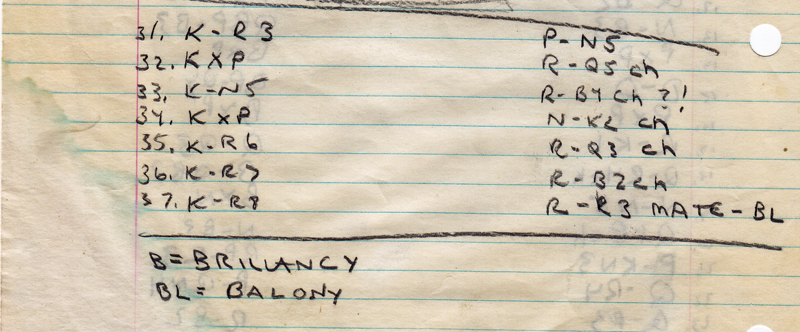

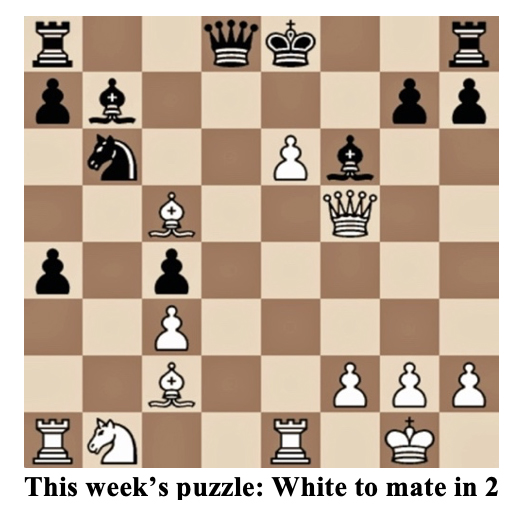

Below is the actual chess notation document inscribed for our game

played on the evening of March 21, 1971:

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________JDA

Front Page

A1

/

Editorials A2 /

Christmas Nostalgia A4 /

Crossword

A5

|

Darrow’s

most enduring contribution was unquestionably the distinctive graphic images

he devised for the

Darrow’s

most enduring contribution was unquestionably the distinctive graphic images

he devised for the  instructing his youngest child in the rules for the gaming nearest and

dearest to his own heart such as gin rummy, pinochle, and perhaps most

prominently, chess. This ensured for him at all times a readily available

game partner and thus the two of us spent many a night at the kitchen table

in the family room at 3219 engaging in various such game competitions. Yet

there was always something of an exalted quality to our chess matches --

that ancient and sublime game that seems to inhabit its own unique

intellectual plane.

instructing his youngest child in the rules for the gaming nearest and

dearest to his own heart such as gin rummy, pinochle, and perhaps most

prominently, chess. This ensured for him at all times a readily available

game partner and thus the two of us spent many a night at the kitchen table

in the family room at 3219 engaging in various such game competitions. Yet

there was always something of an exalted quality to our chess matches --

that ancient and sublime game that seems to inhabit its own unique

intellectual plane.